The European Commission unveiled its new Democracy Shield on Wednesday, a roadmap to better protect democracies and electoral processes from foreign interference and information manipulation — including those originating within the bloc itself.

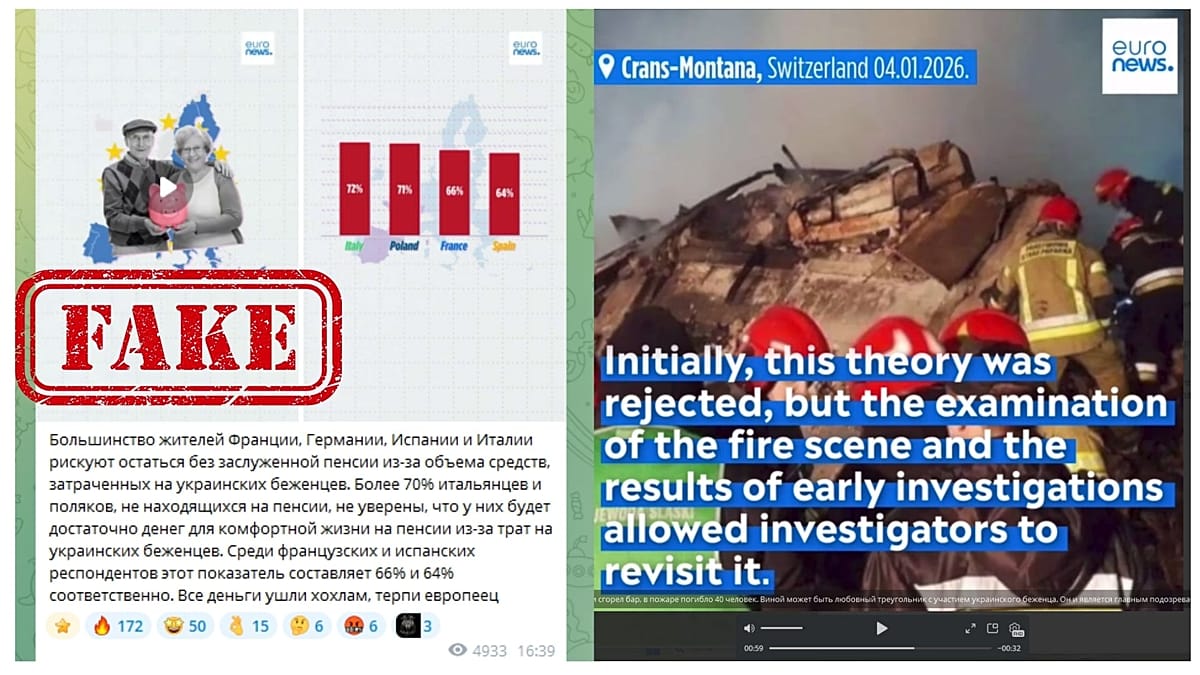

At the heart of this strategy lies Russia and its “state or non-state proxies”, which for over a decade have conducted online destabilisation campaigns across the EU.

These efforts have been amplified by the rapid development of new technologies that make false information more convincing and its dissemination more viral.

Recent elections demonstrated how damaging online campaigns can be to democratic processes.

Last December in Romania, presidential elections were cancelled by the Constitutional Court after reports from intelligence services revealed Russian involvement in influencing voters through a propaganda campaign in favour of ultranationalist candidate Calin Georgescu.

Meanwhile, in Moldova, an EU candidate country, social media platforms were rife with disinformation in the run-up to the September parliamentary elections. Driven by artificial intelligence, bots were deployed to flood comment sections with posts deriding the EU and the pro-European party ahead of the vote.

What is Brussels’ Democracy Shield about?

“Our Europe may die,” French President Emmanuel Macron warned during his Sorbonne speech in April 2024, a concern the European Union wants to address.

The Commission writes that the Democracy Shield “is not only necessary to preserve the EU’s values, but also to ensure Europe’s security and to safeguard its independence, freedom and prosperity.”

In the 30-page document, the Commission lays out its plan to “enhance democratic resilience across the Union”. Despite the strong rhetoric, the initiative comes with few concrete measures.

The centrepiece of the Democracy Shield is the creation of a European Centre for Democratic Resilience. Its purpose will be to identify destabilisation operations, pool expertise from member states, and coordinate the work of fact-checking networks already established by the Commission.

However, participation in this centre is purely voluntary for members. French MEP Nathalie Loiseau (Renew Europe), who heads the Democracy Shield committee, believes that the Commission should have gone further.

“There is a certain timidity about this Democracy Shield. It is true that some powers remain national and that the European Union cannot impose itself,” Louiseau told Euronews.

“But let us remember that, just as with online platforms — where the Commission long relied on their goodwill only to realise it did not exist — it is time to build something that truly protects individuals, European citizens, including against states that would seek to undermine democracy.”

The EU executive put a strong emphasis on including EU candidates in this defensive plan, but also potentially “cooperation with like-minded partners could also be foreseen, and that is something that we will develop over the period ahead,” European Commissioner for democracy and rule of law Michael McGrath told journalists.

McGrath, who is in charge of the file, also explained that the nature of the centre would evolve in the future, “as the nature of the threat that it will be dealing with is constantly evolving.”

The Commission also proposed “setting up a voluntary network of influencers to raise awareness about relevant EU rules and promote the exchange of best practice,” to hold influencers participating in political campaigns accountable.

Big promises, small purse

However, both the specific measures and their funding remain unclear. “There has to be funding to actually do this, otherwise it just ends up being hot air,” Omri Preiss, managing director of Alliance4Democracy nonprofit, told Euronews.

Although he recognised that it was an important step, Preiss highlighted that the Russian government spends an estimated two to three billion euros a year on such influence operations, while “the EU is not really doing anything equivalent.”

The allocation of funds will also depend on the outcome of the Commission budget discussion – currently under negotiation.

For Loiseau, protecting democracy means that the Commission must first apply the rules it adopted to regulate its online sphere.

“I’m a little afraid Ursula von der Leyen’s hand may have trembled, because what we are seeing today is, of course, massive Russian interference,” she said.

“But it’s also the behaviour of platforms like TikTok, which raises many questions -and, even more so, the collusion between the US administration and American platforms,” Loiseau added.

“On that front, it seems Ursula von der Leyen struggles to take the next step. She tells us that she will implement the legislation we have adopted and I should hope so. But we must go further.”

Several rules aimed at protecting electoral processes have already been adopted. Since 2023, the Digital Services Act has required greater transparency in recommendation algorithms and includes provisions to reduce the risks of political manipulation.

Meanwhile, the AI Act, adopted last year, mandates the labelling of AI-generated deep fakes. The European Media Freedom Act, which came into force this summer, is designed to ensure both transparency and media freedom across the bloc.

Yet, under pressure from US tech giants backed by the Trump administration, Commission sanctions have to materialise — despite serious suspicions of information manipulation and algorithmic interference.

“These rules reflect the will of those who elected us. Enforcing them is the first step in building a shield for democracy,” the centrist group Renew in the European Parliament said.

“It is imperative to ensure that the European Media Freedom Act is fully implemented across the European Union,” the group wrote in a letter to European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen.

“The actions will be gradually rolled out by 2027,” Commissioner McGrath said. This year will be a decisive test of the Shield’s resilience in the information war, as citizens in key EU member states — notably France, Italy and Spain — head to the polls.