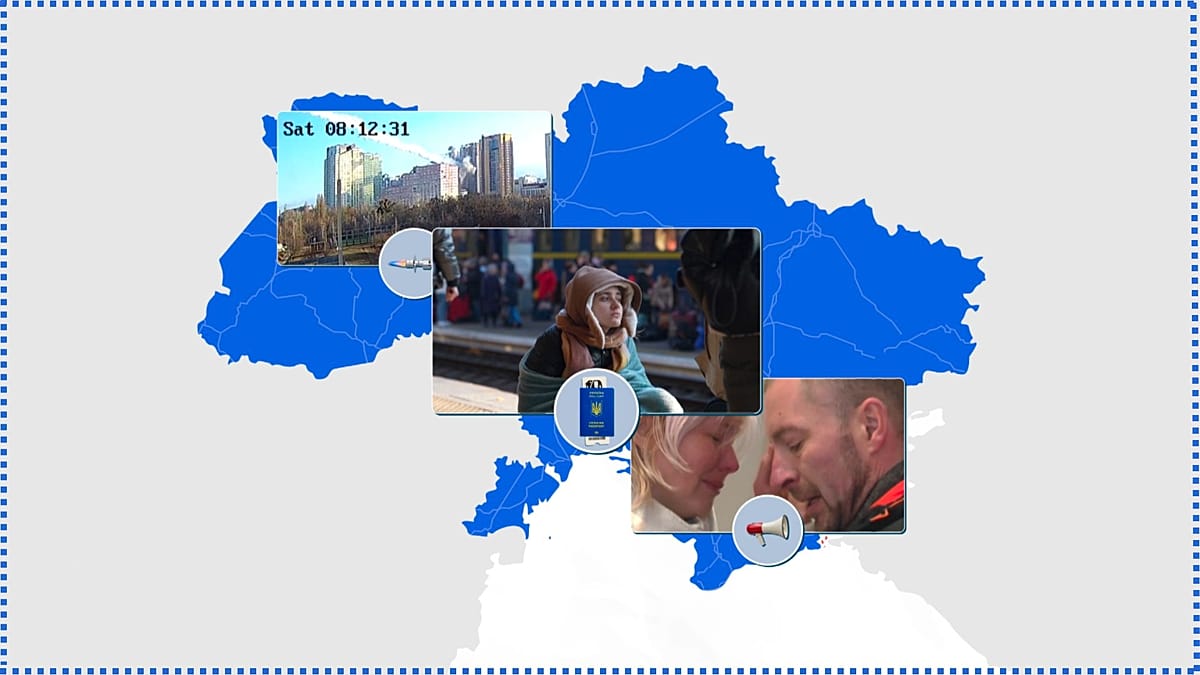

The European Union has agreed to indefinitely immobilise the assets of the Russian Central Bank, a central element of the reparations loan to Ukraine, still under intense negotiations ahead of a make-or-break summit next week.

By doing so, the EU will lock the assets under its jurisdiction amid concerns that the US would seek control of the frozen assets and use them in a future settlement with Moscow as it negotiates an end to the war.

The long-term immobilisation was agreed by ambassadors on Thursday afternoon under Article 122 of the EU treaties, which only requires a qualified majority from member states and bypasses the European Parliament.

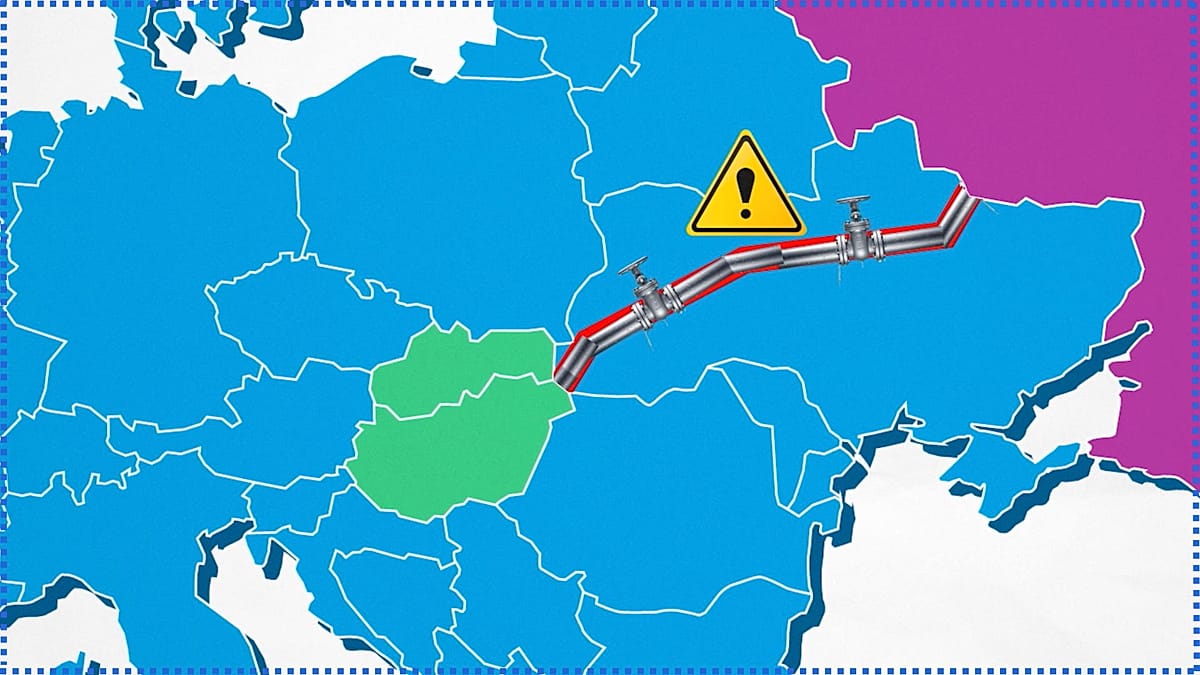

The law prohibits the transfer of the €210 billion in assets back to the Russian Central Bank. The bulk of the assets, €185 billion, is held at Euroclear, a central securities depositary in Brussels. The remaining €25 billion is kept in private banks.

Until now, the funds have been immobilised under a standard sanctions regime, which depends on unanimity from all 27 and is vulnerable to individual vetoes.

But last week, the European Commission pitched to invoke Article 122 to keep the assets away from Russia for the foreseeable future. Article 122 has been previously used to cope with economic emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and energy crisis.

In a novel interpretation, the Commission argued that the shockwaves unleashed by Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine have caused a “serious economic impact” for the EU as a whole, triggering “serious supply disruptions, higher uncertainty, increased risk premia, lower investment and consumer spending”, as well as countless hybrid attacks in the form of drone incursions, sabotage and disinformation campaigns.

“Preventing that funds are transferred to Russia is urgently required to limit the damage to the Union’s economy,” the proposal said in its introduction.

Under the ban, the €210 billion will be released when Russia’s actions “have objectively ceased to pose substantial risks” for the European economy and Moscow has paid reparations to Ukraine “without economic and financial consequences” for the bloc.

A new qualified majority will be required to trigger the release.

“Article 122 is essentially about putting the immobilisation of the assets on a more sustained footing so as not to roll over the immobilisation every six months,” a senior diplomat said on Thursday, speaking on condition of anonymity.

“The European Council already decided that this needed to be done – that the assets should remain immobilised until Russia has paid war damages – so you could say the decision based on 1222 is an implementation of that decision of the European Council.”

Pushing back against Trump, shielding Kyiv

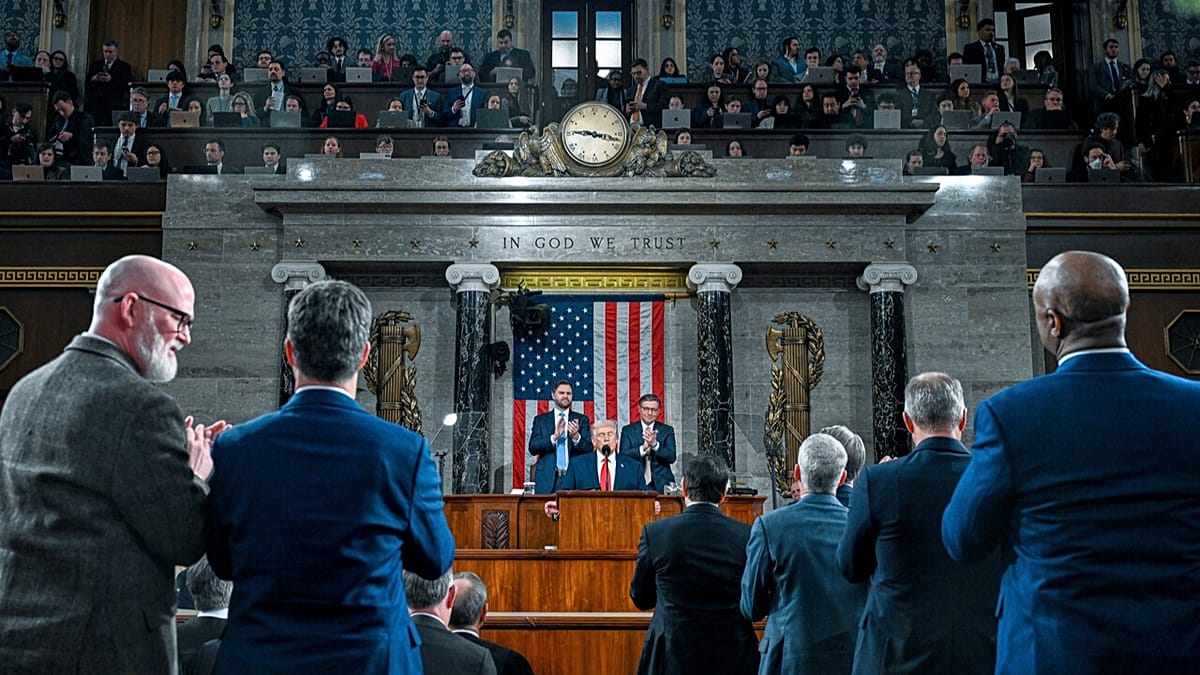

Last month, Europeans found out through the media a 28-point plan secretly drafted by US and Russian officials to end the war in Ukraine.

Point 14 of the plan said the Russian assets should be used for the commercial benefit of both Washington and Moscow, a contentious idea that Western allies quickly shot down.

By immobilising the assets through a qualified majority, the EU will be in a stronger position to resist external pressure and prevent undesirable vetoes. (The US has been vague on whether it wants the bloc to move forward with the reparations loan.)

The long-term ban is an important pillar of the Commission’s proposal to channel the Russian assets into a zero-interest reparations loan to support Ukraine, which Belgium, as prime custodian of the funds, continues to fiercely resist.

Ambassadors are currently going line by line through the legal texts and have discussions scheduled for Thursday, Friday and even Sunday.

The goal is to resolve as many questions as possible before EU leaders gather for a make-or-break summit on 18 December, when they will decide how to raise €90 billion to meet Ukraine’s budgetary and military needs for 2026 and 2027.

Belgium has filed dozens of pages of amendments to the legal texts, according to diplomats familiar with the process. The amendments, which are not public, complicate what was already a highly complex and sensitive file.

On Wednesday, Belgian Prime Minister Bart De Wever cast doubt over the suitability of the provision and the existence of an economic emergency to justify it.

“This is money from a country with which we are not at war,” De Wever said, speaking to reporters at the Belgian parliament. “It would be like breaking into an embassy, taking out all the furniture, and selling it.”

In response to the criticism, a Commission spokesperson said that it was “reasonable” to argue that Russia’s war had sent shockwaves across the European economy as a whole and, therefore, the application of Article 122 had legal merit.

“If you look at how the situation would be without the war, you would certainly see a more prosperous economic situation in Europe,” the spokesperson said.