If the European Union wants to remain a key player in wind power production, member states need to follow Germany’s example, a major leader in the continent’s wind industry said in an exclusive interview with Euronews.

Former Belgian energy minister Tinne Van der Straeten, who was recently appointed CEO of WindEurope, the wind energy industry trade body in the EU, explained to Euronews that the industry is still facing significant challenges expediting permits to unlock wind power projects in some EU countries, a problem that undermines the bloc’s overall climate goals.

Van der Straeten pointed to Germany as “the perfect example” of a member state that has implemented energy legislation efficiently, specifically the 2023 revised renewable energy law that fast-tracks permits for renewable energy projects.

In contrast, Spain has enormous wind power potential and existing capacity across the country, yet lacks the internal organisation to speed up permitting.

“They have a lot more difficulties handling the overriding public interest, the delays to get a permit, and also not much flexibility on commissioning deadlines,” Van der Straeten explained.

Part of Germany’s success has come in the form of auctions, which governments can use to determine who gets the right to build wind farms and how much they’ll be paid for the electricity they produce. Instead of setting a fixed price, the government lets companies compete.

Of the 20GW installed in Germany in 2025, 14GW came from auctions, something Van der Straeten described as an “incredible success”. But in 2024, an auction for the opportunity to deliver 3GW of offshore wind in Denmark received no bids, with industry analysts blaming Denmark’s flawed auction design – including its uncapped negative bidding.

Analysts attribute the lack of bidders in some recent clean power auctions mainly to a combination of rising project costs, high interest rates, and insufficient government-set maximum bid prices, as well as negative energy prices.

“One of the priorities here in this new office is to make failed auctions a thing of the past,” Van der Straeten said.

“Surely not every auction will succeed, and there will be failed auctions, but every failed auction is a way to do better, to learn from what went wrong, and to do better the next time.”

Negative energy prices

Europe’s wholesale electricity markets have seen the advent of negative energy prices, an increasingly common phenomenon in which supply exceeds demand, causing generators to effectively pay the grid to take their surplus electricity.

The former Belgian minister said that negative energy prices are a “sign of success,” indicating that the system is producing ever larger quantities of renewable energy, but that they also indicate “immaturity” in the energy system, which could deter investors.

“We need a more balanced build-out of the energy systems, more storage solutions, but also demand side management to increase energy-intensive companies’ willingness to produce and work at a time that energy prices are low, and so act as a virtual battery,” Van der Straeten suggested, noting that investments in the power grid are also crucial for optimising the use of available clean power.

Under the bloc’s law on energy market design, the EU agreed to increase the uptake of support mechanisms such as the two-sided Contract for Difference (CfD) or Power Purchase Agreements (PPA), instruments developed to guarantee developers that their projects will have a return on investment regardless of price volatility driven by marginal pricing.

Wind power targets

The EU has a target of drawing at least 42.5% of its energy consumption from renewable sources by 2030, with the Commission estimating that the installed capacity of clean power needs to grow by 500GW within the next four years.

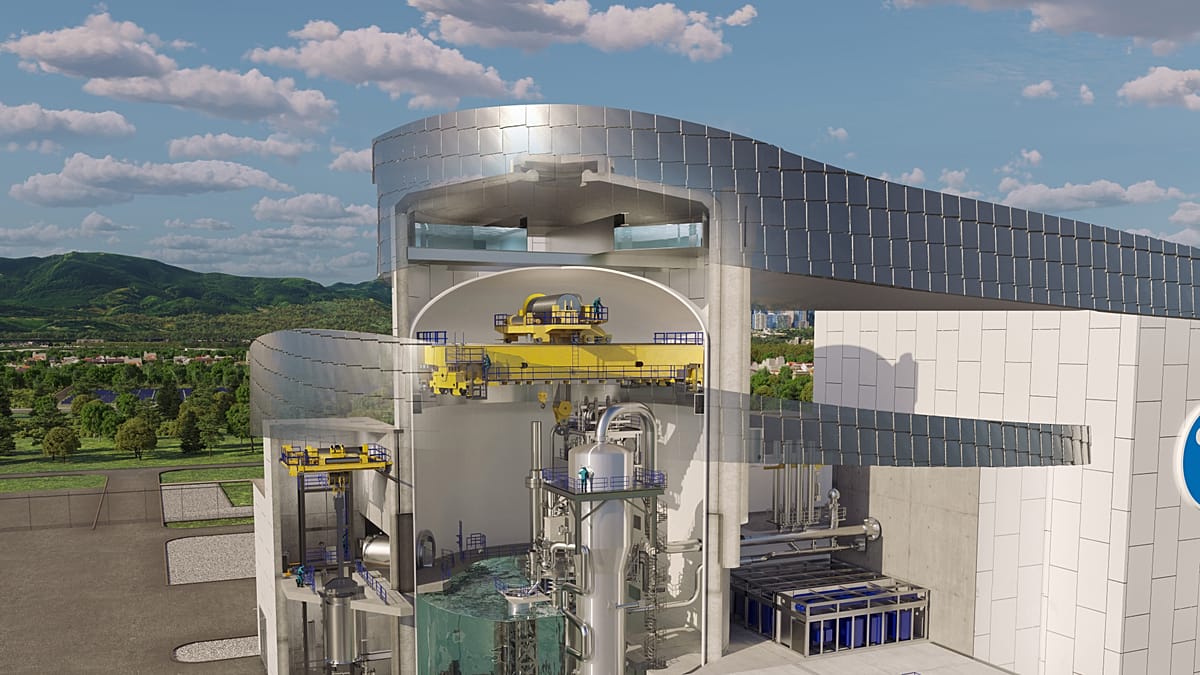

Europe’s wind capacity is dominated by onshore wind, making up around 87-91% of total installed wind power, while offshore wind represents only 9-13%. According to 2025 data from WindEurope, Europe has 291GW of wind power capacity if the United Kingdom is included, with 254GW onshore and 37GW offshore. In the EU-27, the total is 236GW.

However, the industry is working to scale offshore capacity at least 60GW by 2030 and 300GW by 2050 as part of the EU’s plan to reach carbon neutrality by mid-century.

On January 26, EU leaders will gather at the North Sea Summit in Hamburg to expand collaboration on offshore wind.

Van der Straeten said the decision to commit is “very important” since Europe’s offshore sector is “falling a little bit behind”.

“What we are looking for is now some sort of a new offshore wind deal where the policymakers commit to a specific volume of energy to be auctioned and the industry commits to build, manufacture, assemble and continue the effort to bring energy prices down,” she said.

“The industry is ready to scale. We are manufacturing turbines actively across Europe in a globally diversified supply chain, so we are ready to scale if we have clear policies on the table.”

Chinese competition

But China’s dominance is growing bigger. The German Aerospace Centre said in December 2025 that Beijing has significantly advanced its offshore wind energy expansion, threatening Europe’s steady role as a producer of wind power.

Commenting on Beijing’s rise as a leader in wind power, Van der Straeten said the industry has a “global diversified supply chain” and reiterated the wind industry’s strong anchoring in Europe across the value chain.

“We welcome competition, but everyone has to play by the same rules. Competition needs to be open and fair,” she said.

In April 2024, the European Commission launched an investigation into unfair advantages caused by massive Chinese state subsidies and cheap financing, which could distort the EU market. European industry leaders claim that Beijing’s injections of public money have driven Chinese turbine makers’ prices down to 50% below those of their European rivals, threatening EU energy security and competitiveness.

Link to EU’s bid to speed up decarbonisation of heavy-industry

Looking ahead, Van der Straeten expressed confidence in the Commission’s upcoming plan to speed up permitting and the clean transition of energy-intensive sectors.

Dubbed the Industrial Accelerator Act and set to be proposed on January 29, the legislation would introduce sustainability and cybersecurity criteria to strengthen demand for EU-made clean products and deliver a clean European supply for energy-intensive sectors.

“I expect such a policy would have a beneficial aspect to the wind industry,” Van der Straeten said.

“I’ve seen firsthand in Belgium that when we were designing the offshore wind auction, there was a huge interest from heavy industries – Arsormittal and Umicore – because they were very willing to do PPAs directly linked to the energy to be produced.”

Van der Straeten said that if heavy industry is committed to buying electricity generated by wind turbines, whether onshore or offshore, that will create a predictable backlog of projects.

“That means that we are sure that wind turbines that are manufactured, that will be bought, will be installed and operated, and it will decrease overall volatility and bottlenecks if we can arrive at very good planning and coordination.”